THE TRUTH ABOUT TELEHEALTH

Its issue isn’t the technology. It’s the human.

The mass-scale adoption of telehealth (or telemedicine/e-medicine) will be a lasting legacy of the global pandemic. But its rapid uptake gave rise to challenges – some of which are highlighted in our article ‘Post-pandemic recovery: What’s in store for healthcare?‘ To gain insights into these challenges ‘on the ground’, we put telehealth to the test. We surveyed nearly 1,000 people from Publicis Groupe companies across the UK, US and Canada about their personal experiences of e-consultations. What worked? What didn’t? Would they do it again?

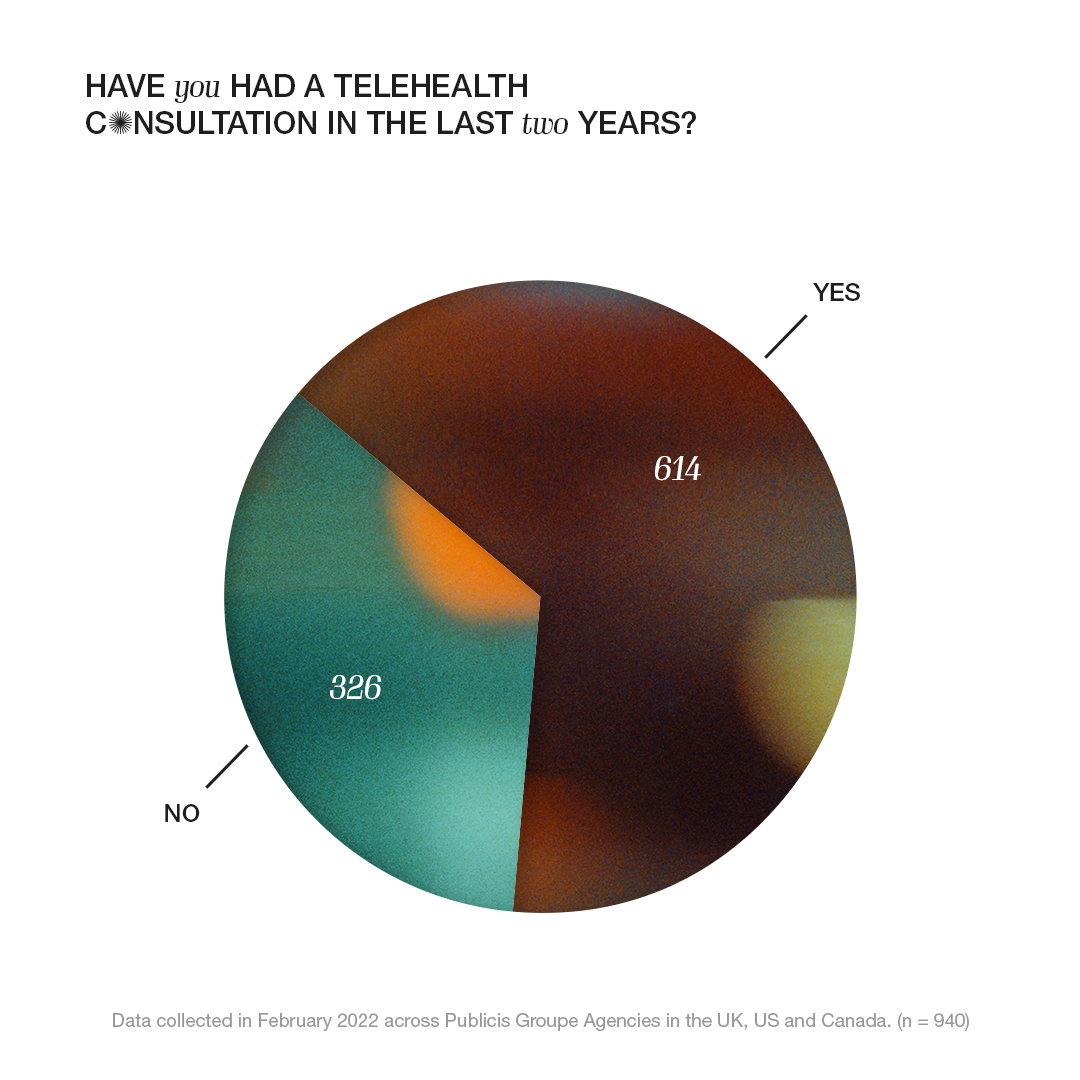

How mainstream are telehealth consultations?

Over 60% of our respondents reported having at least one telehealth consultation in the last two years, which aligns with evidence from the United States of a sharp rise in the availability of remote healthcare services: a recent McKinsey Physician Survey found that 83% of healthcare providers offered virtual services in 2021, compared with only 13% in 2019.

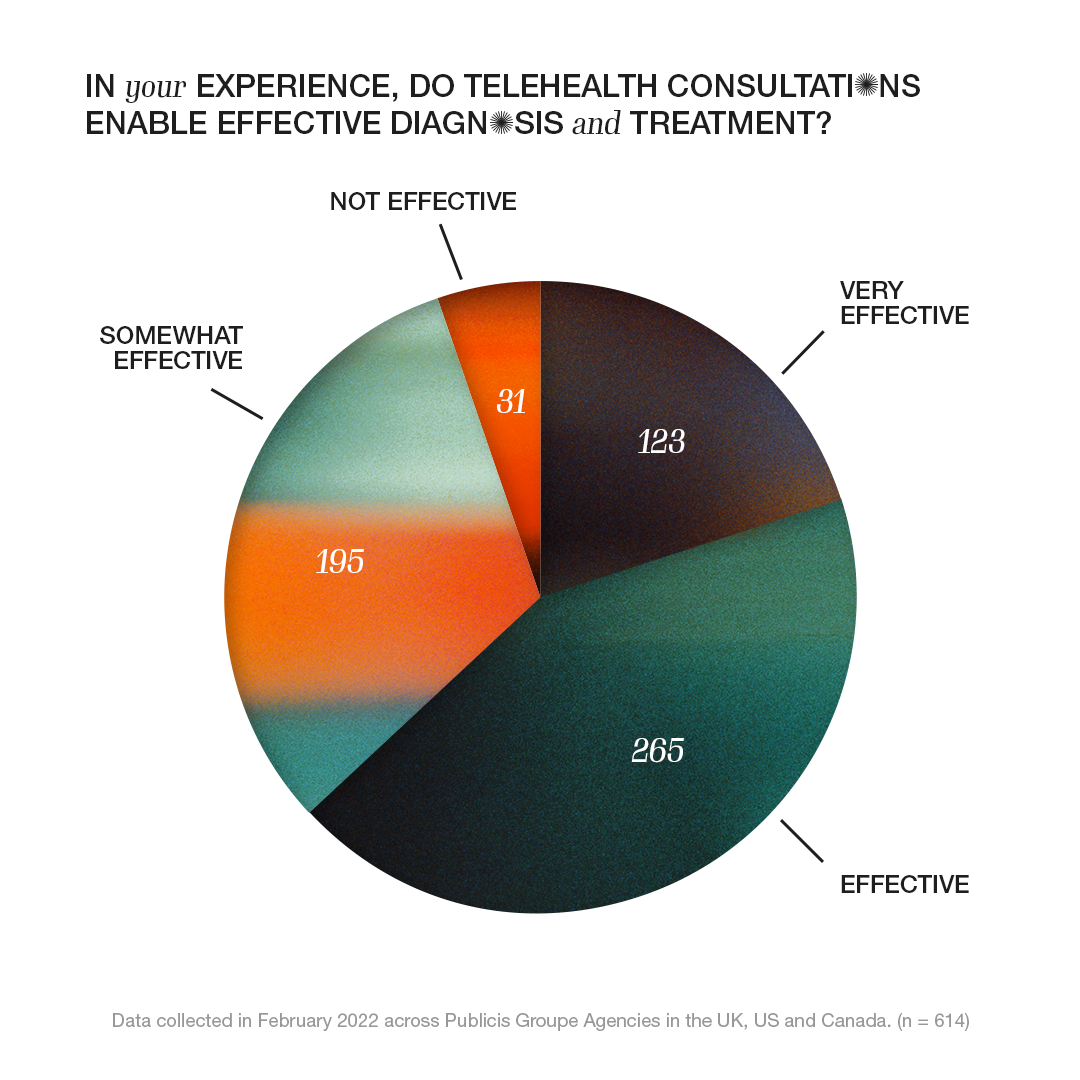

What can telehealth not do?

Sixty-three percent of those with direct experience of telehealth consultations in our survey believed they could lead to effective diagnosis and treatment. Yet this optimism only held true in a limited set of circumstances. Individual testimonials illustrate some of the more obvious challenges that emerged as virtual appointments replaced in-person visits. Current telehealth services are ill-fitted to any situation requiring a physical examination or procedure, with examples ranging from blood tests to orthopaedic range of motion assessments.

Testimonials describe telehealth as best suited for communication and information-sharing, or simpler transactions, such as a follow-up consultation with a known healthcare professional or a repeat prescription.

The missing human connection

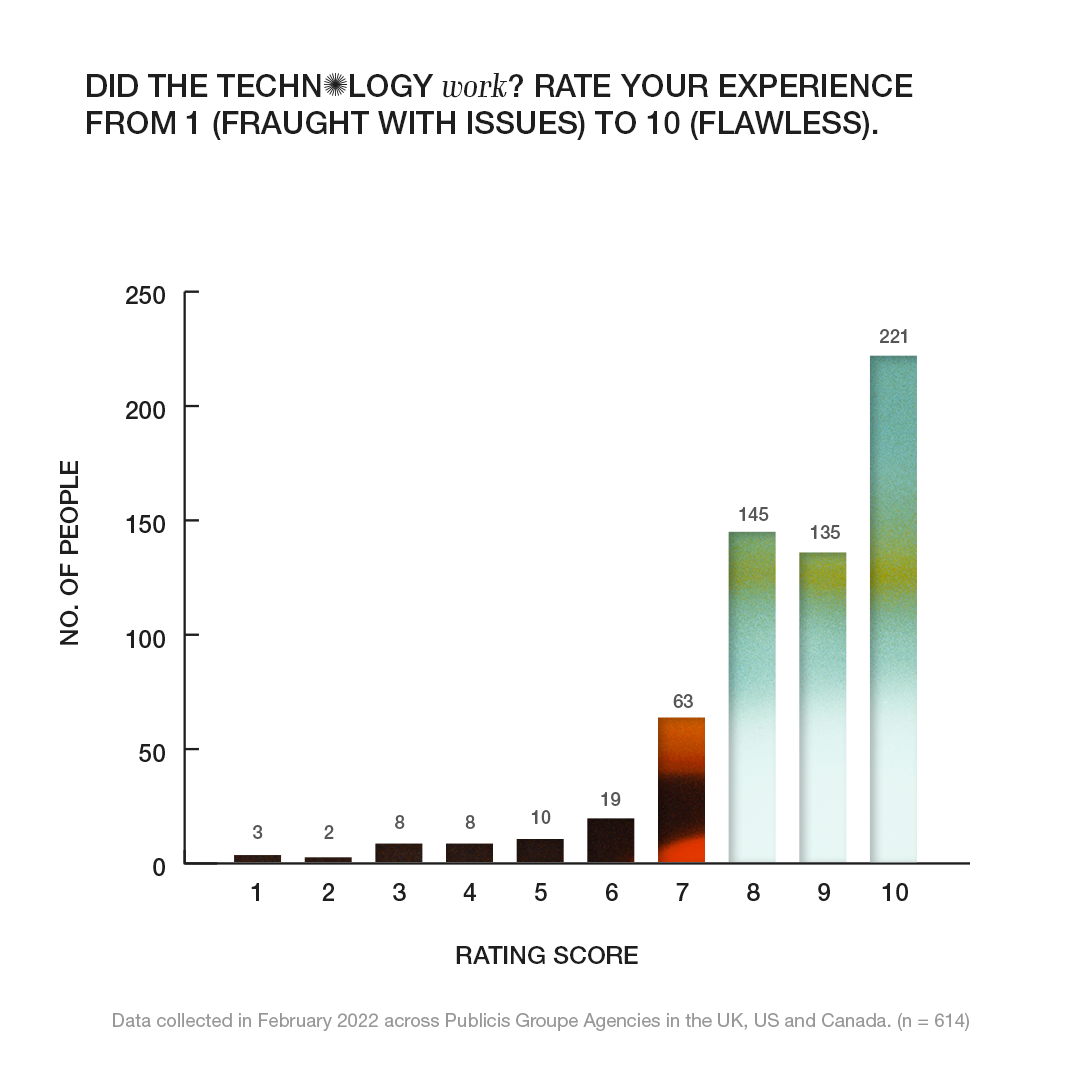

Perhaps surprisingly, technology is not the main pain point. In fact, over 80% of survey respondents reported having a positive experience with the technology. What stood out instead was the disappearance of the human dimension in consultations, with a negative impact on the quality of the interaction and overall effectiveness of the session as a result.

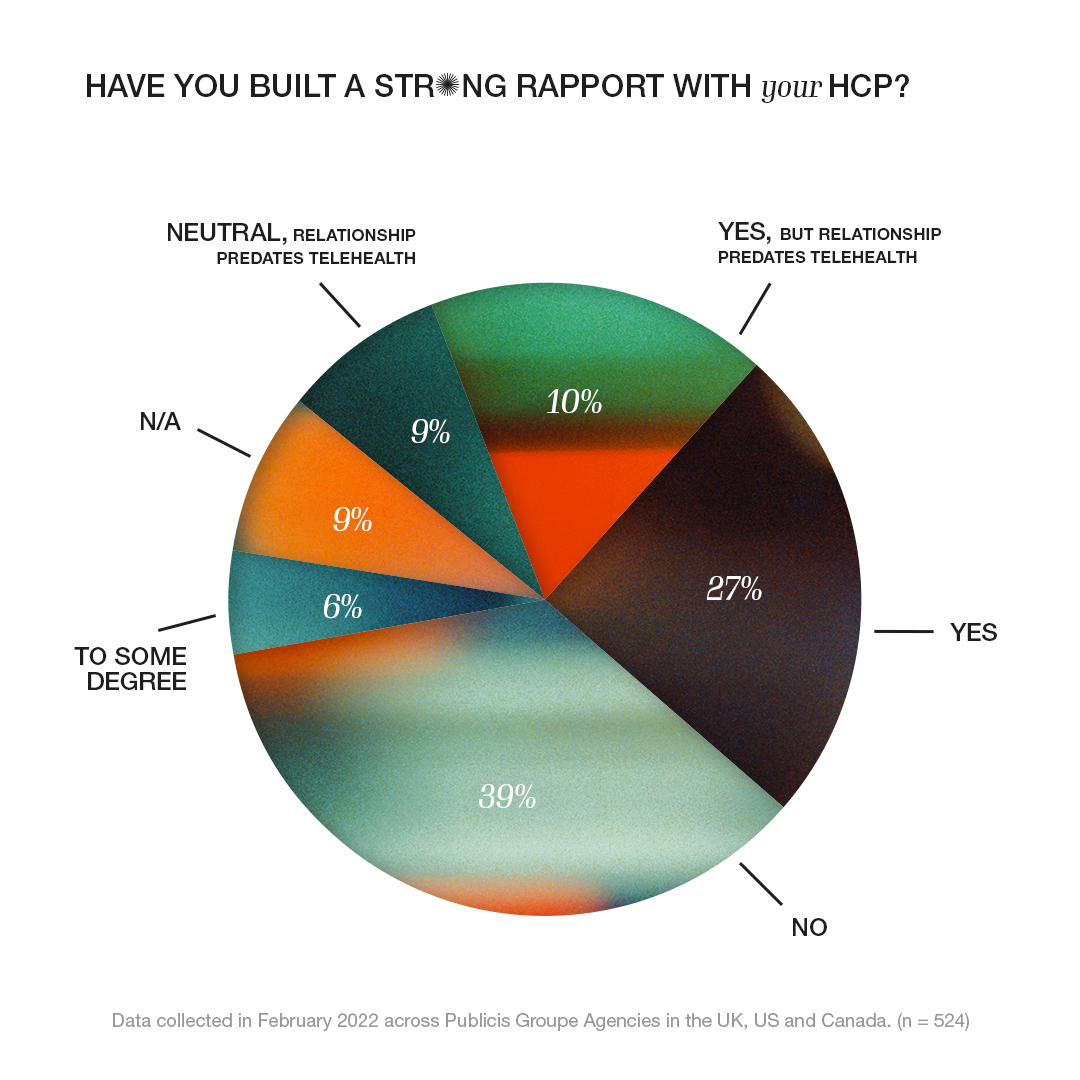

The lack of human connection, empathy, and personalisation doesn’t just have an impact on the patient/HCP relationship. It can also lead to missed opportunities to diagnose or investigate issues early on. Whilst patients in the UK may be used to short consultations – a 2017 study published in BMJ Open found that the average GP consultation in the UK lasted just over nine minutes – this isn’t the case everywhere. The same BMJ study found that the average consultation length in the United States was just over 20 minutes.

Telehealth consultations may be more regimented, with participants in our survey widely reporting feeling rushed during such appointments. Depending on the provider, participants also reported having little to no opportunity to follow up with the same doctor. Only 27% of survey respondents unequivocally reported having built a strong rapport with a healthcare professional using telehealth.

How do we keep healthcare human?

Just as patients have had to change the way they manage their own health over the last two years, HCPs have had to adapt to a new style of consultation. To keep healthcare human as telehealth is increasingly being adopted, their role will be crucial.

“A lot of HCPs will need to develop new skills to be able to manage patient consultations better on the phone,” commented Lymphoma Patient Advocate, Penny Clarke. “They need to use open checking questions to ensure understanding, and make sure that the patient has had time to ask about any queries or concerns before calls are concluded.”

David Griffiths, GP, Chief Medical Officer at Teladoc UK, also commented: “We will need to think about how we share information when consulting remotely – it’s hard to use pictures to demonstrate things over the phone for example – and what the patient gets to take away. There are also big questions to ask in secondary care. I wonder if hospital specialists may be less used to assessing risk remotely than GPs and they work within more inflexible systems, which have evolved over decades to deliver in-person care.”

Improving or widening health inequality?

There is a learning curve for both HCPs and patients to use telehealth efficiently. Even so, certain groups of patients are likely to benefit disproportionately. Inequalities in broadband internet access and digital literacy will need to be addressed for telehealth to be accessible to the widest group possible. Digital inclusion, which is already being recognised as a social determinant of health by national organisations like the American Public Health Association in the United States and NHS Digital in the UK, must be a focus for next generation telehealth.

Digital accessibility will also be key. One respondent in our survey, who is hard of hearing, highlighted the challenges experienced due to their reliance on captioning during video calls. As most telehealth platforms do not currently offer closed captioning, they told us that they had to rely on mainstream platforms like Google Meet to use captions – potentially sacrificing privacy in the process.

“Overall, the technology response to support communication during the pandemic was good, but the rapid deployment need meant solutions were generalised for the masses,” observed Drew Owen, Chief Scientific Officer at Langland and Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Lead Champion for the Publicis UK Health Practice. “Now that we have the basic platforms, deeper thinking is needed to make them fully inclusive and equitable for everyone. The Microsoft Teams update to include closed captioning is a nice example of how the tech is catching up to support broader needs.”

So what comes next?

Telehealth isn’t a silver bullet. “A lot of work still must be done to help patients and HCPs to make the most of the new tools, which in turn presents many opportunities for medical education to support HCPs to optimise patient engagement through telehealth,” comments Rebecca Nunn, Senior Account Director in Medical Strategy & Education at Langland. “This may be establishing best-practice through indication- and locality-specific round tables, taking into consideration the cultural nuances that provide the backdrop to remote, virtual consultations; or the provision of remote consultation training to help refine the physician’s approach – considering how to effectively build a positive therapeutic relationship with the patient through verbal and non-verbal modes of communication, to deliver both the emotional care needed as well as information relating to the patient’s condition.”

In turn, these medical communications activities will also provide insights to enhance the technology used by the platforms hosting telehealth consultations – already we have heard requests for telehealth applications and online portals to accommodate frequent image uploads by patients to help practitioners monitor conditions, as well as better subtitling for the hard of hearing and user-friendly interactivity designed to create privacy, humanise and improve the rapport between HCP and patient.

New possibilities may soon emerge too, with many providers already filing trademarks for new goods and services in the metaverse, a virtual universe perhaps best described as a 3D model of the internet. The US-based giant CVS is one example, having recently filed to trademark its pharmacy and health clinics in the metaverse (Ad Age). In this scenario, virtual or extended realities could become a core part of patients’ care plan and give telehealth a whole new dimension, ultimately improving HCP and patient relationships and providing a better quality of patient-centred care.

© 2023 Langland | A Publicis health company